ITS works 24/7 to protect Syracuse University email systems from outside infiltration

Illustration by Dani Pendergast

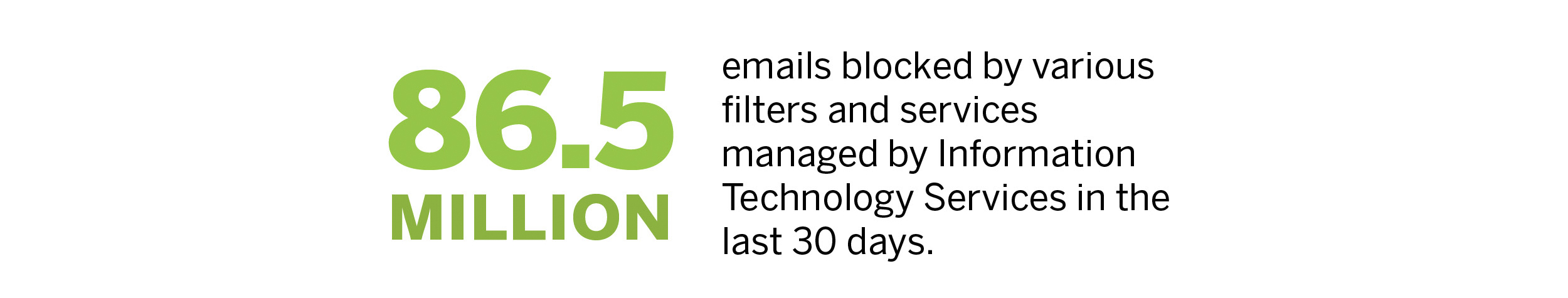

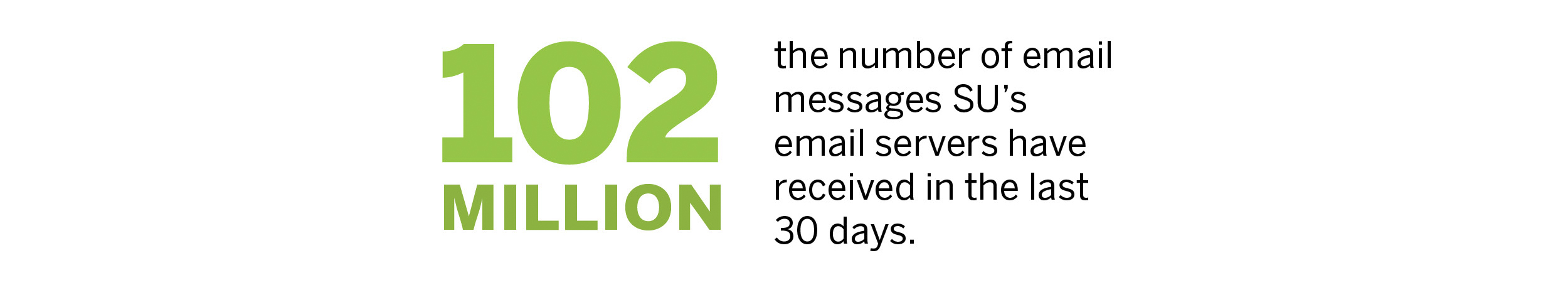

About 84 percent of emails sent to Syracuse University email addresses in the past 30 days have not been delivered.

In that time, SU’s email servers have received more than 102 million email messages, meaning only 16 percent of the emails sent to SU addresses are accepted and delivered. The other 84 percent of emails — more than 86.5 million emails in total — were blocked by the various filters and services managed by Information Technology Services.

Protecting university email accounts — about 105,000 mailboxes — is a 24/7 battle and ITS uses complex software to help stop infiltration to the systems.

Andrew Joncas, manager of core infrastructure services, and his team can work securely from anywhere in the world, but on the SU campus, they do 90 percent of their work in Machinery Hall.

Joncas and his six-person team manage many services on the SU campus, including lower-level services like infrastructure, storage and processing power and higher-level services like email.

Two separate email systems are used for SU: one for students and one for employees. Student email is routed through the university’s email servers to the Microsoft cloud email system — known as SUmail — where individual mailboxes are managed. Employee mail, however, is housed in Microsoft Exchange and supported by SU’s virtual cloud.

“ITS has less visibility into and control over the student email environment at Microsoft,” members of the team said in an email. “While this limits our ability to protect student email directly, we are confident in the standards and practices Microsoft has in place.”

SU uses several security methods to protect both student and employee emails, including firewalls, access control through NetID and password security, encryption and filters.

All access to all services is controlled through something called two-factor, Joncas said, which is the concept of “something you know and something you have.” For example, the “something you know” is a person’s username and password, Joncas said, whereas “the something you have” is something that looks like a thumb drive, but is a cryptic key.

Chris Finkle, communications manager for ITS, said this two-factor security makes it very difficult for someone who is not a member of Joncas’ team to even log in to one of the systems and do something.

The most common type of attack Joncas’ team sees is on the individual level is “phishing attacks,” in which hackers convince people in some way to give up their username and password. This often happens when a person receives an email linking to a website that looks authentic, when in reality it was built by a hacker.

But, Joncas said, ITS has scanners programmed for its email systems that help filter out these “phishing attack” patterns. He said the scanners are like doctors — they only know about the things they’ve seen before but can try to use heuristics to defend against the attack, just like a doctor would.

In terms of protecting student and employee emails against spam, Finkle said both the student and employee email servers have “fairly robust” spam filters. But, he said, the amount of spam a person receives is dependent on how “promiscuous” they are on the Internet.

Finkle explained that hackers will often randomly generate emails in order to send spam and viruses. Colleges and universities can be “sitting targets” in these cases because student and employee email addresses usually end in .edu, making it easier for hackers to randomly guess.

However, Finkle said ITS is able to catch a lot of these randomly generated spam emails on the servers’ filters.

ITS also encrypts all email communications with SU’s systems, Joncas said, so it’s important for SU students and employees to stay within the university’s systems. ITS cannot monitor security problems if they happen in another mail system, such as Gmail.

The team said keeping ITS up-to-date with the latest methods hackers are using to gain access to systems and services is a challenge they deal with. Every month ITS performs software patches on the SU systems, including the mail systems. This means they update the system’s software. They also subscribe to notifications about new infiltration techniques, or hacks.

In addition, the infrastructure of SU systems are penetration-tested by outside security inspection companies hired by ITS. The security inspection companies will attempt to hack SU’s systems in various ways and at the end, ITS will receive a report card about the strength of the systems. Joncas said the tests are a good way to make sure ITS is using an adversary that works well.

These infrastructure tests happen typically on a yearly basis, Joncas said, but each time, they focus on different aspects due to the large size of SU.

He added that ITS will usually give these companies information to make them better hackers, which in turn improves SU’s systems.

“They’re on the inside track in the hacking communities,” Joncas said. “… So that tests our ability and our preparedness for things that haven’t come out yet.”

Joncas said protecting email and educating users are only two parts of what it takes to keep the systems secure. People also need to be vigilant in their own lives and with their own devices in order to better secure the technology they use, he said.

“It is a cat and mouse game. It is an arms race and every day we have to up our game to make sure we are one step ahead of theirs,” Joncas said. “It’s one of those things that you have to be vigilant every day, because if you slip, they’ll get you.”

Published on October 8, 2015 at 12:13 am

Contact Sara: smswann@syr.edu | @saramswann