Jim Boeheim stands by the Carrier Dome court and shrugs off question after question as he watches his players warm up before practice.The questions are the same ones he’s been asked over and over again — the same ones he’s downplayed for years. The longtime Syracuse icon stretches his lips and tilts his head, continuing to understate everything about the 2-3 zone that one former Big East head coach called one of the greatest weapons in the history of the sport.

“The zone is like the Mariano Rivera cutter,” said ESPN analyst Fran Fraschilla, a former St. John’s head coach. “Mariano will throw the cutter 3-2, two outs in the ninth, and that’s how Jim’s zone is. If man-to-man is a fastball, normal zones are curveballs, Jim’s zone is the Mariano Rivera cutter, nearly impossible to hit.

“You may break a bat on Jim’s zone on occasion but you’re not hitting grand slams on it.”

Boeheim has been studying the 2-3 zone defense for 52 years to be exact — longer than about 70 percent of the American population has been alive. There may be no icon in sports history more closely associated with a singular tactical operation.

And yet there was no eye-opening moment of enlightenment. The man described by others as ingenious and masterful describes the growth of the zone as gradual. He talks about the defense not the players. And he even presents the system as simple and replicable — though that’s just his inclination to skate over and simplify it.

From Boeheim’s first days trying to crack the Lyons Central junior varsity zone in practice, to orchestrating Syracuse through his first 20 years, the head coach accrued a vast wealth of knowledge. He’s absorbed every possible wrinkle and rotation on the hardwood and instructed hundreds of players how and when to utilize them.

That’s why, around 1996, he decided to switch to the zone full time.

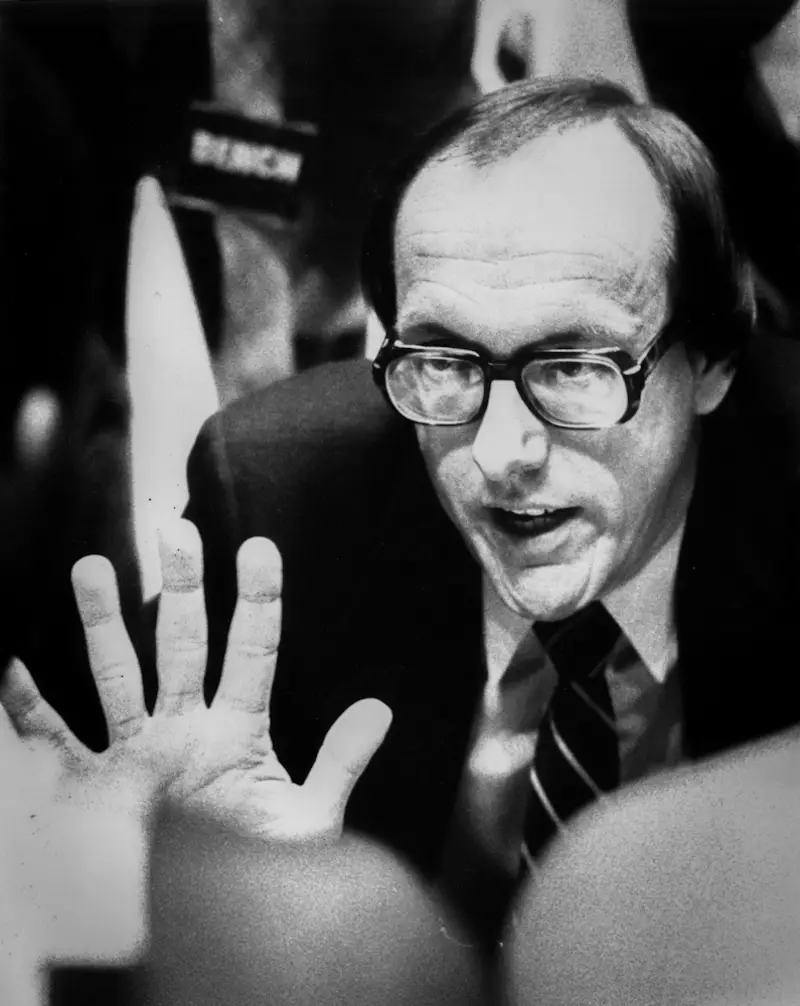

File Photo

“Finally it dawned on me,” said Boeheim in a candid moment after his team’s 61-50 win over Indiana in last year’s Sweet 16, “after about 27 or 28 years that if we played zone all the time and didn’t waste time playing man-to-man and put some wrinkles in the zone, that our defense would be better.”

But before all the flash and fame, Boeheim was a scrawny, 6-foot-3 guard for Lyons Central High School. At about 155 pounds, he was a pretty good physical model for the guards he would recruit half a century later.

But he was more offensive minded. Had there been a 3-point line, teammates agreed his team-leading scoring average as a senior would have been higher.

His coach, Dick Blackwell, first introduced the concept of zone defense to Boeheim and six of his friends who played together from sixth grade through graduation.

“He taught me a lot about basketball,” Boeheim said.

Teammates Don Oakleaf and Mike DeCola remember their sophomore year when the deft-shooting Boeheim was bumped up to varsity. In practices, the JV squad would often play a zone and have to extend their guards up on Boeheim.

“Personally I don’t think there’s any question that his experience in high school carried over,” Oakleaf said. “He had plenty of time to see how effective they were.”

Courtesy of Don Oakleaf

Blackwell used the 2-3 and 2-1-2 zones about 30 percent of the time against most teams, but predominantly in the team’s two games against rival Newark Valley each year.

Oakleaf — the center who was only slightly taller and about 20 pounds heavier than Boeheim — said the team had to play zone against a stockier opposing big man.

“We never lost to Newark,” Oakleaf said with a chuckle.

Coming to Syracuse as a freshman in 1962, Boeheim’s next coach was Fred B. Lewis. He was more of a yeller than Blackwell. And he played more zone, but relied most heavily on full-court pressure.

The same rotations Boeheim practiced in high school carried over to college, where he starred alongside fellow freshman and roommate Dave Bing.

Jimmy was not a great individual defensive player, but he was very smart. He knew how to play angles offensively and defensively.

Dave Bing

Bing said that as a player who thrived with the ball in his hands, Boeheim’s ability to communicate with him on the court was crucial to the team’s success.

His perception was unmatched by other teammates, and as Boeheim moved into coaching, Bing said it allowed him to slow the game down and notice smaller details of the defense.

“I think he just picked up on what they were doing,” Bing said, “the little nuances that we didn’t do well back then.”

He was hired as a graduate assistant by Roy Danforth in 1969 and became a full-time assistant soon after. Boeheim said he often asked Danforth to play more zone. And once Danforth left for Tulane in 1976, Boeheim did it himself.

Close friend P.J. Carlesimo, who was an assistant coach at Fordham at the time, remembers how quickly Boeheim’s first few teams mastered the zone.

“A lot of those teams were not nearly as athletic as the later teams,” Carlesimo said, “but they always played the zone very, very well.”

Boeheim utilized the zone more than his predecessors, but not all the time. He encouraged his teams to trap in the low post and the corners — the same fundamental defensive principles Blackwell outlined when he started playing.

Defending the corner 3

Defending the low post

Boeheim plugged players of all different shapes and sizes into his system.

The Lee brothers, Jimmy and Mike, highlighted Syracuse teams in the early 1970s before giving way to the Louis and Bouie show. Louis Orr and Roosevelt Bouie revolutionized fast-break offense coming out of the zone.

And some of that duo’s success stems back to a conversation Boeheim had with Bouie, his first-ever recruit and a 6-foot-11, 225-pound speedster of a center.

It was Bouie’s freshman year in 1976 and he was struggling to adjust to college life, as well as the zone’s intricate defensive slides.

The troubles shook his nerves. So Boeheim told him not to overthink the technical movements. Just focus on moving quickly.

“If you can work so hard in practice every day that when you finish practice it’ll take you 15 minutes before you can bend over and take your shoes off,” Boeheim said, “what more can I ask of you?’

“That took a big weight off my shoulders,” Bouie said.

File Photo

As the years went on, Boeheim gradually ran more and more zone. He learned to work in each rotation during the preseason and integrated a six-on-five drill that allowed the first-team defense to prepare for the next game.

If the upcoming opposition featured a sharpshooter, Boeheim would pluck another player from the sideline — Leo Rautins in Bouie’s era — and have them prepare the guards for extra-fast slides.

If the upcoming opposition featured a high-post threat, Boeheim would place an extra man there.

He even learned to adapt with the game. When the 3-point line was introduced in 1986, Boeheim pushed his wings up to defend the perimeter and dropped his center.

If you want to learn zone, there’s only one zone to study. That’s Jim Boeheim’s 2-3 zone.

Seth Greenberg, ESPN analyst & former NCAA head coach

The zone defined the heyday of Big East basketball for some, as many coaches labored to find a way to beat it.

Pete Gillen, who was an assistant coach at Villanova (1978–80) and Notre Dame (1980–85) before taking the helm at Providence from 1994–98, recalled a ploy he took from longtime Louisville head coach Denny Crum: back-screening the weak-side guard.

Weak-side guard screen

Six days after getting stomped by the one-loss Orangemen on Jan. 7, 1998, Gillen’s 6-7 Providence squad dropped 76 points in the Carrier Dome en route to a mammoth upset.

“We probably weren’t a very good team, but we beat them up there,” Gillen said.

Boeheim had plenty of games like that during his first 32 years of growing the zone. In truth, he had plenty of every kind of game during that span. And through it all, the zone proved to be the key ingredient in his winning formula.

As the Carrier Dome horn blew, indicating the start of practice, Boeheim raised his eyebrows before answering one last question in typical Boeheim fashion.

So why did you decide to go to the zone full-time?

“I just thought we were best with it.”

Published on January 28, 2014 at 3:25 am

Contact Stephen: sebail01@syr.edu | @Stephen_Bailey1